The Wistar Institute

Revolutionizing Cancer Treatment: Wistar and Accelerated Biosciences Collaborate to Pioneer Transformative Immune Cell Therapies

PHILADELPHIA — (July 10, 2024) — The Wistar Institute (“Wistar”) is pleased to announce a research collaboration with Accelerated Biosciences Corp. (“Accelerated Bio”) aimed at creating a groundbreaking platform based on human trophoblast stem cells…

The Wistar Institute Recruits Jozef Madzo, Ph.D., as Director of Bioinformatics

PHILADELPHIA — (July 1, 2024) —The Wistar Institute is pleased to announce the appointment of Jozef Madzo, Ph.D., to the faculty as an assistant professor and Director of Bioinformatics. Dr. Madzo will lead and oversee Wistar’s bioinformatics projec…

Wistar President’s Society Members Gather for Special Event Featuring Dr. Paul Offit

Nearly 100 steadfast members of Wistar’s President’s Society and honored guests gathered at The Wistar Institute to attend this year’s President’s Society Dinner for an evening of community and reflections on the scientific journey. Dr. Dario Altier…

Why this Wistar Scientist sees hope for an HIV cure

Dr. Luis J. Montaner, D.V.M., D. Phil., is the Herbert Kean, M.D., Family Professor; vice president of Scientific Operations; associate director for Shared Resources at the Ellen and Ronald Caplan Cancer Center; director of the HIV-1 Immunopathogene…

The Wistar Institute Receives $10 Million Donation

PHILADELPHIA — (June 18, 2024) — The Wistar Institute received a $10 million donation from an anonymous donor who previously committed $20 million to support Wistar’s new Center for Advanced Therapeutics. This now $30 million gift to Wistar’s Bold S…

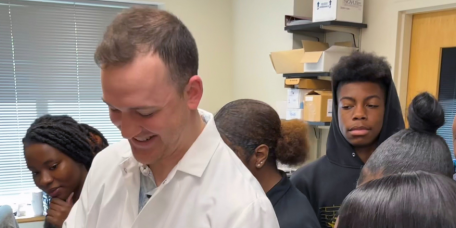

Research in the Classroom: Wistar and Collaborators Enhance Experiential Learning in The Life Science Classrooms of G.W. Carver High School

[pictured: George Washington Carver High School students observe Wistar’s Andrew Milcarek, Ph.D. in the lab] Philadelphia’s George Washington Carver High School of Engineering and Science is a criteria-based admission school that enrolls stude…

Wistar Scientists Develop Novel Antibody Treatment for Kidney Cancer

PHILADELPHIA — (June 04, 2024) — Advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is a deadly form of kidney cancer with few treatment options; even with new immunotherapies, only around one in 10 patients ultimately survive.

Wistar Research Identifies Mechanisms for Selective Multiple Sclerosis Treatment Strategy

PHILADELPHIA — (May 28, 2024) — The Wistar Institute’s Paul M. Lieberman, Ph.D., and lab team led by senior staff scientist and first author, Samantha Soldan, Ph.D., have demonstrated how B cells infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) can contri…

Wistar Melanoma Researchers Discuss Risks and Solutions for Melanoma Awareness Month

Three of The Wistar Institute’s foremost melanoma researchers: professor Meenhard Herlyn, D.V.M., D.Sc.; associate professor Jessie Villanueva, Ph.D.; and assistant professor Noam Auslander, Ph.D. discussed the progress and potential in melanoma res…

Revealing Biology’s Hidden Patterns: Wistar’s Dr. Noam Auslander on the Power and Potential of Machine Learning

Dr. Noam Auslander, Ph.D., is assistant professor of the Molecular and Cellular Oncogenesis Program at the Ellen and Ronald Caplan Cancer Center. She focuses on developing machine learning methods to understand the factors driving cancer development…