The Art and Science of Dr. Livio Azzoni

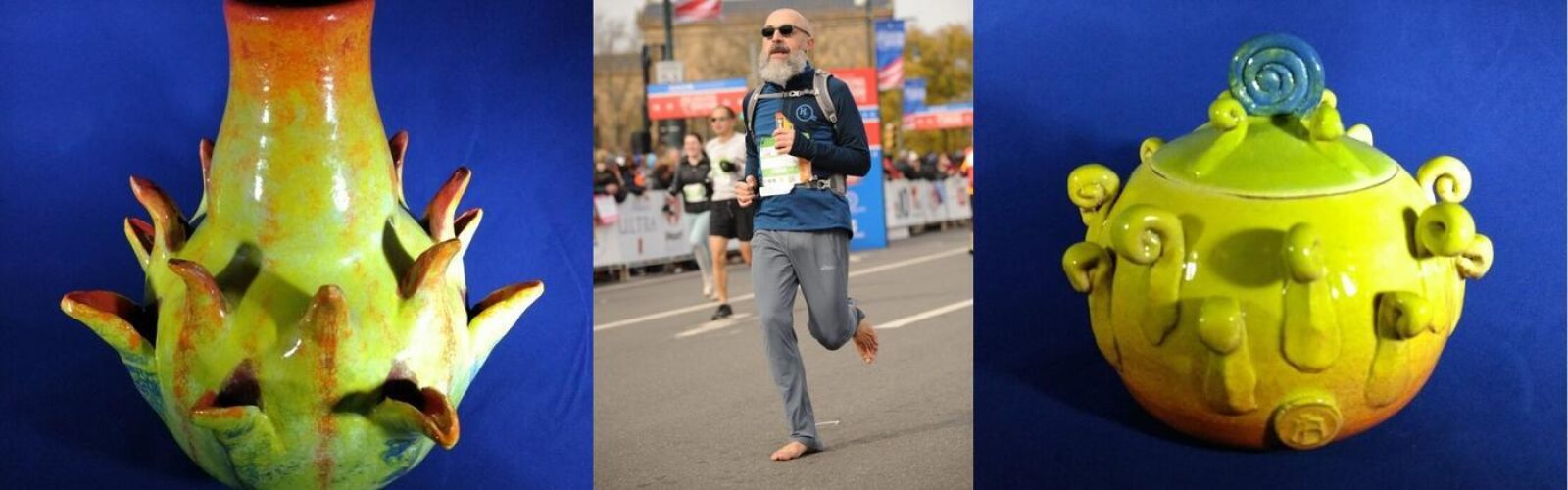

Dr. Livio Azzoni racks up 20+ miles a week running to and from work at The Wistar Institute. This senior staff scientist in the laboratory of Dr. Luis Montaner took up running 13 years ago because he was, “Growing, but in the wrong direction. [I] was growing in girth so I decided to do something, and it stuck.” What’s more intriguing is that Livio runs barefoot. He runs the Schuylkill River Trail from East Falls into West Philadelphia. He hops over glass shards and other treacherous street bits, running rain or shine, and stopping only when temperatures dip below 30 degrees. Though it is this scientist’s preferred running style he concedes it might not be for everyone.

“I must be very focused on where I step. I also practice cyclic breathing (for example, breathe in for four steps and out for four steps). I think this combination is very meditative—it’s yoga in motion: instead of holding a pose, you’re moving. It helps focus on experiencing the moment, so it’s sort of a mindfulness exercise,” said Livio.

For this immunologist moving the mind through heightened creativity and ability seems to be a running consequence.

Livio is a researcher in the Montaner HIV research lab. The lab is a BEAT-HIV Delaney Collaboratory with international impact and a finely tuned team of researchers conducting collaborative, cure-directed research in a transformational program nationally and internationally renowned. Beyond carrying out basic (foundational) research and translational research with an eye toward new drugs and therapies, lab members contribute to population studies and plan and execute state-of-the-science clinical trials. With links connecting local and global partners, the lab maintains strong ties with the local community, community partner organizations, federal HIV/AIDS organizations, major academic science groups, and advocacy groups. The goal is an HIV cure.

Wistar scientists are a high-achieving lot even outside the many lab research hours they spend. Livio is one of those high functioning, immensely creative individuals whose rigorous work life parallels a creative and unconventional private life—pursuing art through pottery and mindfulness through long distance running.

Livio’s path to science was extraordinary. His mother and father moved back to Torino, Italy, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo just before he was born. In high school he enjoyed biology and chemistry and interned at a local hospital. Since students were not allowed to work with patients, Livio interned in the hospital lab. It’s there he developed his clinical lab interest. Livio was the second person in his family to attend university. Next, he obtained his M.D. at the University of Torino and then went on to mandatory military service in the Italian Army. “My time in the Army was the only time I ever actually practiced as a doctor—to 2,000 fellow Army cadets,” said Livio.

Supported with money saved from his military service Livio volunteered at the Pathology Institute for the University of Torino which launched him to the Ph.D. program at the Cancer Institute at the University of Genoa under mentor-scientist-physician Dr. Manlio Ferrarini. From there Livio left for the U.S. and cut his teeth on basic immunology studying natural killer cells at the bench in the Wistar lab of the late Dr. Bice Perussia. He followed Dr. Perussia to the Jefferson Cancer Center, working in basic research for the next 10 years and eventually pursuing a certificate in Management from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania.

As his interest evolved to a more clinical focus, in 2000 Livio returned to Wistar joining the Montaner lab to run a clinical study in South Africa just six years after apartheid ended. He worked on multiple projects studying HIV pathogenesis, intermittent treatment and recovery outcomes of people living with HIV.

“This project focused on underserved populations. At the time, very little clinical research was being done in these people that could benefit them directly” said Livio. “Up to 2003, no antiretroviral treatment (ART) was available to the vast majority of HIV-infected individuals in South Africa. Our group worked closely with the doctors spearheading the effort to force the South African government to provide free ART treatment. Our study allowed many individuals who would not have qualified under the government rollout to obtain ART as recommended by the WHO guidelines”

South Africa was a country of contrasts. A modern healthcare delivery infrastructure was in place, but only accessible to White South Africans. When apartheid ended Black South Africans gained access to a modern but undersized healthcare system, which struggled to deliver access to millions of HIV-infected individuals (an estimated 5.3 million in 2002, according to UNAIDS). This was a uniquely productive time to be on the ground working with communities with healthcare access.

“Many people were living in poverty and treating people was a luxury, and obviously, HIV wasn’t the only disease and resources were limited,” said Livio. “Apartheid had kept Black and “Colored” South Africans segregated in all aspects of life, including healthcare. With the end of apartheid, all South Africans gained access to the formerly segregated modern healthcare facilities. It was a huge challenge on resources and infrastructure, but also an extremely rewarding time—a very fertile ground for research and for ideas.”

Twice a year Livio traveled to South Africa, but he also had projects running locally through Montaner lab connections to Philadelphia FIGHT, a nonprofit advocacy organization providing a myriad of health, social and education services to people living with HIV as well as the greater Philadelphia community.

Currently Livio works on several eclectic clinical research projects. “The study of pathology and human disease, if nothing else, gives you empathy,” said Livio. “Documenting the physiology of a normal body layered with studying pathology of that body, is where data comes in. The data collection and characterization of data for use includes a broad range of scientific interests, that complements my varied education.”

Though possessing an immunologist’s mindset when it comes to pathogenesis and disease outcomes, he has a deep interest in data sciences and creating data-driven approaches to analyze and illuminate particular results. The Montaner lab creates clinical studies and Livio works with colleagues to design what data to collect and how best to collect it. Working alongside Luis Montaner, he can “big picture” what needs to be collected, understands the scientific process and how to analyze the data.

Livio credits Luis’ foresight to invest in data for their clinical trial research. Their lab’s expertise has led to the creation of Wistar’s Biomedical Research Support Facility, which provides scientists with the infrastructure to support clinical trials including data collection, control, analysis, site and regulatory support. Livio spends 50 percent of his time running this core facility.

“You need to know the processes by which data are collected,” said Livio. “In clinical research there’s a very specific path to ensure that everybody is tested and everybody’s participation produces actionable data. Essentially, it’s designing the system that collects the data, collecting the data, cleaning the data, quality management, quality control, and then finally having usable data.”

Livio believes there is a misconception that one needs to be a genius to be a scientist—if he can do it anyone can. Being a scientist really means following the passions, interests and curiosities that we all have. Livio lives that belief, whether it’s studying management to improve his skills, or becoming an amateur potter who throws large vessels on the pottery wheel and hand builds remarkable creations. His broad and varied scientific career keeps life interesting and mirrors a vibrant personal life.

If data were life, Livio keeps his data diverse and the digital noise low. He says nothing is canonized because it’s all variable and it all depends on the operations you have running. He may be talking data, but he thinks it is a good life lesson as well.

View Flickr photo album here.