Deja Flu: Revisiting Influenza 100 Years Later

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the 1918 Spanish lnfluenza outbreak, a pandemic that affected millions around the world. Over the decades, advancements in vaccine medicine have saved countless lives, but new tools are still needed to prevent the flu in vulnerable individuals and to make the vaccine more effective. Wistar hopes its new generation synthetic DNA technology will provide a future strategy for the global toolbox against flu.

Now identified as a strain of the H1N1 flu virus, the Spanish flu was an exceptionally lethal strain that took more lives than World War I and World War II combined — killing 20 to 50 million people in mere months — and indiscriminately claimed not only vulnerable individuals but also strong, seemingly healthy young adults. *

The first wave of the outbreak was a mild form that appeared and spread throughout the United States from birds and farm animals to humans. Then as troops deployed during World War I, it traveled to Europe. The second wave of flu became the deadliest—killing people who would otherwise be categorized as healthy—and the effect of military movement helped the virus spread ultimately to Asia. With no treatment or vaccine in place, there was no way to effectively control the spread.

Philadelphia was one of the many urban areas hit hardest by the 1918 pandemic: more than 50,000 people became infected and 12,000 people died.** At a Liberty Loan Parade taking place in the heart of the city along Broad Street, more than 600 people caught the flu while attending the event. Three days after, the city’s 31 hospitals could not keep up fast enough with the demand to take care of the sick.

100 years later, where do we stand with influenza prevention and what strategies are now available to protect us?

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) are two global multinational nonprofit organizations advancing science in the form of experimental research that could best respond to a future outbreak before it becomes a pandemic. They, along with health officials and epidemiologists, monitor how emerging viruses can become global health and economic threats. As the world becomes more and more interconnected and borderless, much can be gleaned from past outbreaks like the Spanish flu with the hopes to use that knowledge to prevent future pandemics.

David Weiner, Ph.D., executive vice president of Wistar, director of Wistar’s Vaccine & Immunotherapy Center, and the W.W. Smith Charitable Trust Professor in Cancer Research, and colleagues are funded by the Gates Foundation and CEPI to advance synthetic DNA-based vaccine and antibody technology.

Every year, multiple strains of the flu virus circulate. Six to nine months before the season starts, researchers make an educated guess about which strains will be most prevalent. However, the flu virus can rapidly mutate throughout the season, causing a vaccine directed against a specific circulating strain to become ineffective. If this happens, there is not enough time to make a new vaccine, since the process traditionally takes five to six months.

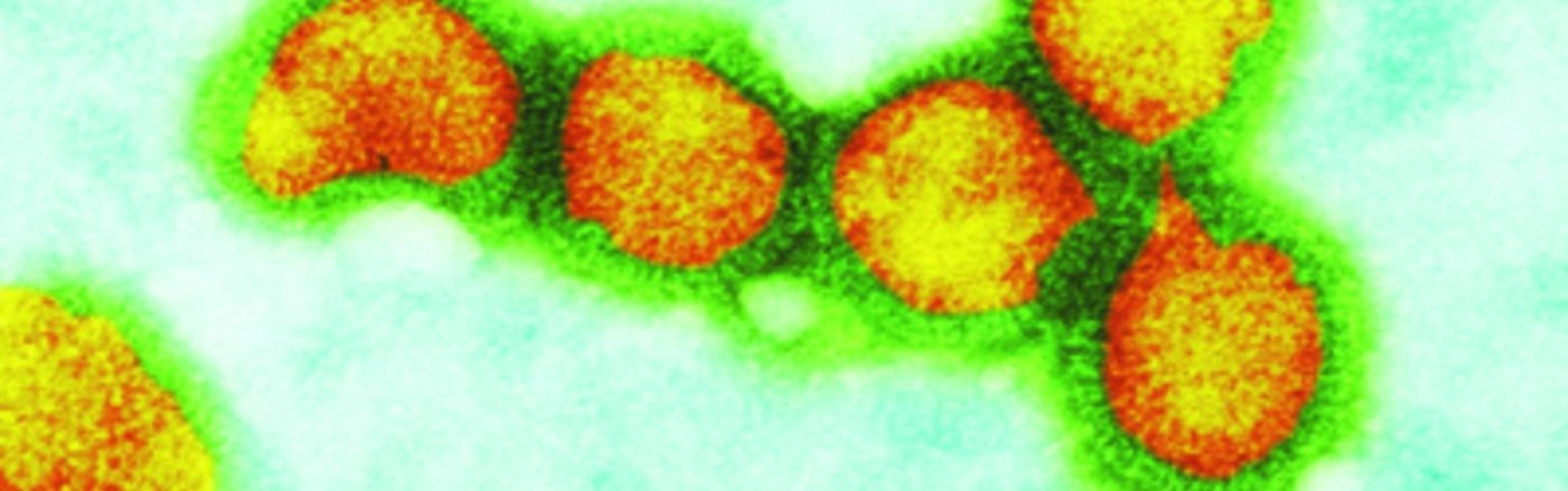

The Weiner Lab recently published research in the journal Human Gene Therapy on a synthetic DNA vaccine against influenza A, which is responsible for the most severe influenza seasons of the past decade. Using this technology, Weiner created a vaccine cocktail targeting the most probable flu strains circulating during a season, which can offer broad protection against influenza A viruses. The synthetic DNA vaccine being developed by Weiner and his collaborators delivers genetic instructions into the muscle cells to make them produce specific influenza antigens that trigger an anti-flu immune response. Their studies showed that this approach induced increased immunity and protection compared to traditional vaccine technologies.

Though this technology has not been tested in humans for the flu, it is very promising and provides a glimpse of what a new generation of flu vaccine could be: conceptually more safe, potent, faster to make, and easier to distribute and house—a promising strategy against the global threat of influenza.

*Center for Disease Control and Prevention

** “The Flu in Philadelphia,” PBS.org and “Philadelphia was the epicenter of a deadly worldwide flu epidemic 99 years ago,” phillyvoice.com